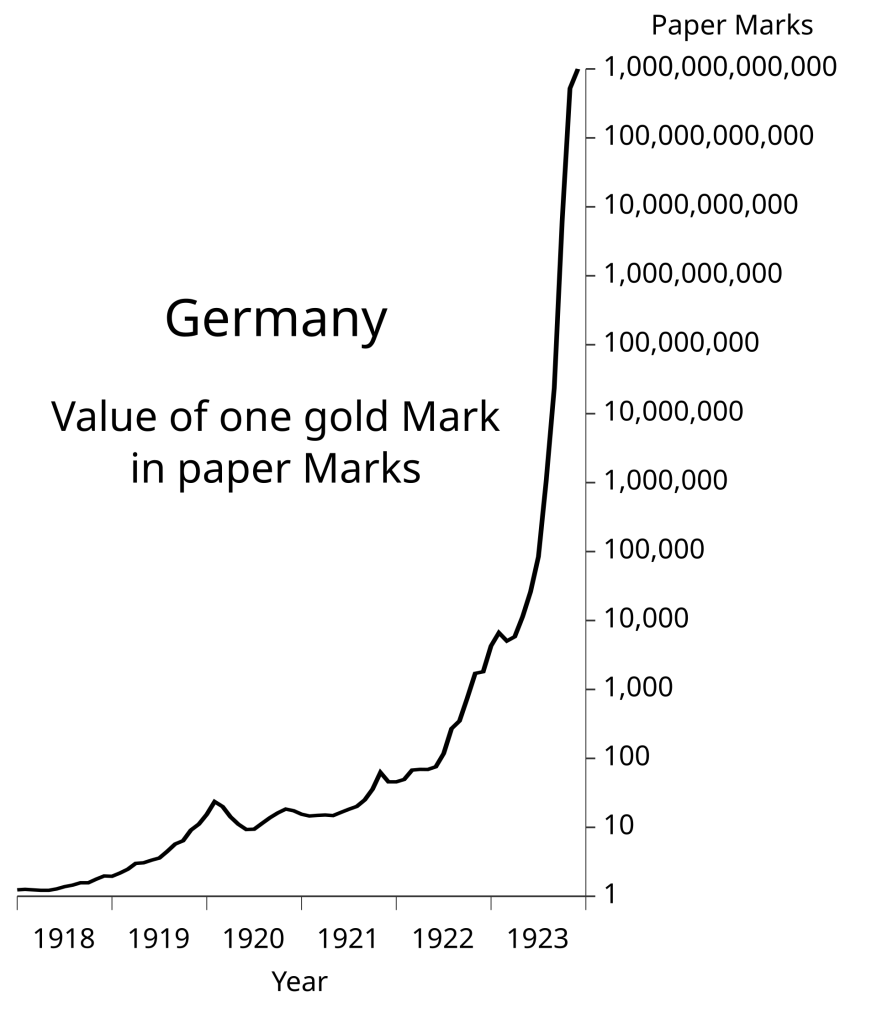

In the years after the First World War, Germany faced countless social, political and economic challenges that brought it to the brink of complete collapse more than once. Civil unrest and crippling debt plagued the nation, while the severe terms of the Treaty of Versailles caused prices to increase by over one trillion times from 1918 to 1923.

After the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II and the end of the German Empire, a National Assembly was held at the town of Weimar and a democratic constitution was created. This resulted in the formation of the Weimar Republic, a provisional government that guided Germany through this dire period and ushered in the ensuing prosperity of the Golden Twenties. In the midst of civil unrest, hyperinflation and imminent revolution, the leaders of the Weimar Republic continued to govern the nation with conviction and efficiency. The pivotal decisions of its leaders allowed Germany to endure one of the most turbulent periods in its history. So how exactly did Germany recover from WWI?

How Did Germany Recover From Hyperinflation?

Germany famously experienced severe challenges with inflation in the years after WWI. Excessive wartime spending and the depletion of its gold reserves had utterly devastated the economy. To make matters worse, the harsh terms of the Treaty of Versailles forced Germany to pay a further $6.6 billion in economic reparations. Despite this crippling debt, however, the Weimar government actually managed to delay hyperinflation for much of this period until they could participate in borrowing programs and stabilise the currency.

In the first two years after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, the Weimar government was relatively successful in managing inflation given the present circumstances and Germany’s crippling debt. By mid-1921, the value of the Papiermark had remained mostly stable at a conversion rate of around 90 marks per dollar. The Weimar government later took advantage of Allied officials withdrawing from most of Germany, making minimal reparation payments throughout 1921 and 1922 due to reduced supervision. This sustained the value of the Papiermark for an additional year, although hyperinflation eventually ensued in 1923. This was primarily due to the French occupation of the Ruhr region in Germany, alongside excessive printing of the Papiermark to exchange for foreign currency.

The cabinet of newly appointed German chancellor Gustav Stresemann, however, was quick to act. Working alongside the President of the Reichsbank, Stresemann swiftly introduced the Rentenmark on November 20, 1923. This was a new currency backed by industrial and agricultural land that was mortgaged to the gold standard. The Retenmark stabilised the German economy, cutting twelve zeroes from price tags and laying the foundation for borrowing schemes such as the Dawes Plan, which further reduced reparation payments for the nation.

Solutions to Political Instability

So how did Germany recover from the widespread political instability after WWI? We must once again look to the leaders of the Weimar Republic for answers. Shortly after the Kiel Mutiny and the November Revolution of 1918, Germany was in a state of utter disarray, and someone needed to fill the power vacuum from Kaiser Wilhelm II’s abdication. On 19 January 1919, the Council of People’s Deputies, a provisional government set up by workers’ councils in Berlin, organised an election for a Weimar National Assembly. For the first time in history, a democratic system of government would lead Germany, an astonishing development given the widespread unrest and revolution only months prior. The German people voted for a variety of political parties in the 1919 election, with the hugely popular left-wing Social Democratic Party winning 163 seats in the National Assembly or 38% of the total vote.

On 6 February 1919, the National Assembly convened at the German National Theatre in the town of Weimar for the first time. They began with the task of writing a constitution for Germany, which was to be a democratic federal republic with a president and a parliament. After the completion of the Weimar Constitution, the duties of this provisional National Assembly were finished and it was formally dissolved. There would be a second federal election on 6 June 1920, in which parties ran for election in the new Reichstag, which took the place of the National Assembly. The Weimar leaders navigated through this period of political unrest with astounding organisation and efficiency, aiding in Germany’s recovery from WWI.

Violent Responses to Civil Unrest

Countless uprisings and revolts plagued Germany after the end of WWI. From 5-12 January 1919, a revolt known as the Spartacist Uprising broke out in Berlin between the Social Democratic Party, which favoured a social democracy, and the Communist Party, which wanted a government similar to Lenin’s Bolsheviks in Russia. The provisional government swiftly crushed the Spartacist Uprising through the use of violence in an event later referred to as Bloody Week, with troops killing up to 200 individuals to quash the rebellion. This authorised act of force was ultimately necessary to ensure that rebels did not prevent Germany’s recovery from WWI.

On 13 March 1920, another left-wing revolt known as the Ruhr Uprising took place in the Ruhr region of Germany, in which around 50,000 workers went on strike as part of the ‘Ruhr Red Army’. The government attempted to negotiate with these workers through the Bielefeld Agreement, but its failure led to another 300,000 workers joining the strike. On 2 April 1920, General Oskar von Watter, by command of the Weimar government, led Reichswehr units into the Ruhr region and committed mass executions on the revolting Ruhr Red Army, killing over 200 soldiers and 1,000 workers in the ensuing massacre.

On 8 November 1923, around 2,000 members of a small right-wing extremist group called the Nazi Party, led by Adolf Hitler, surrounded the Feldherrnhalle in the centre of Munich in the Beer Hall Putsch. Munich law enforcement had no choice but to exercise force in order to protect the government building, resulting in a shootout that left 14 Nazis and four police officers dead. This ruthlessness of the Weimar government ensured that insurrection did not topple the delicate balance of power in Germany.

Read more: The Insight Corner