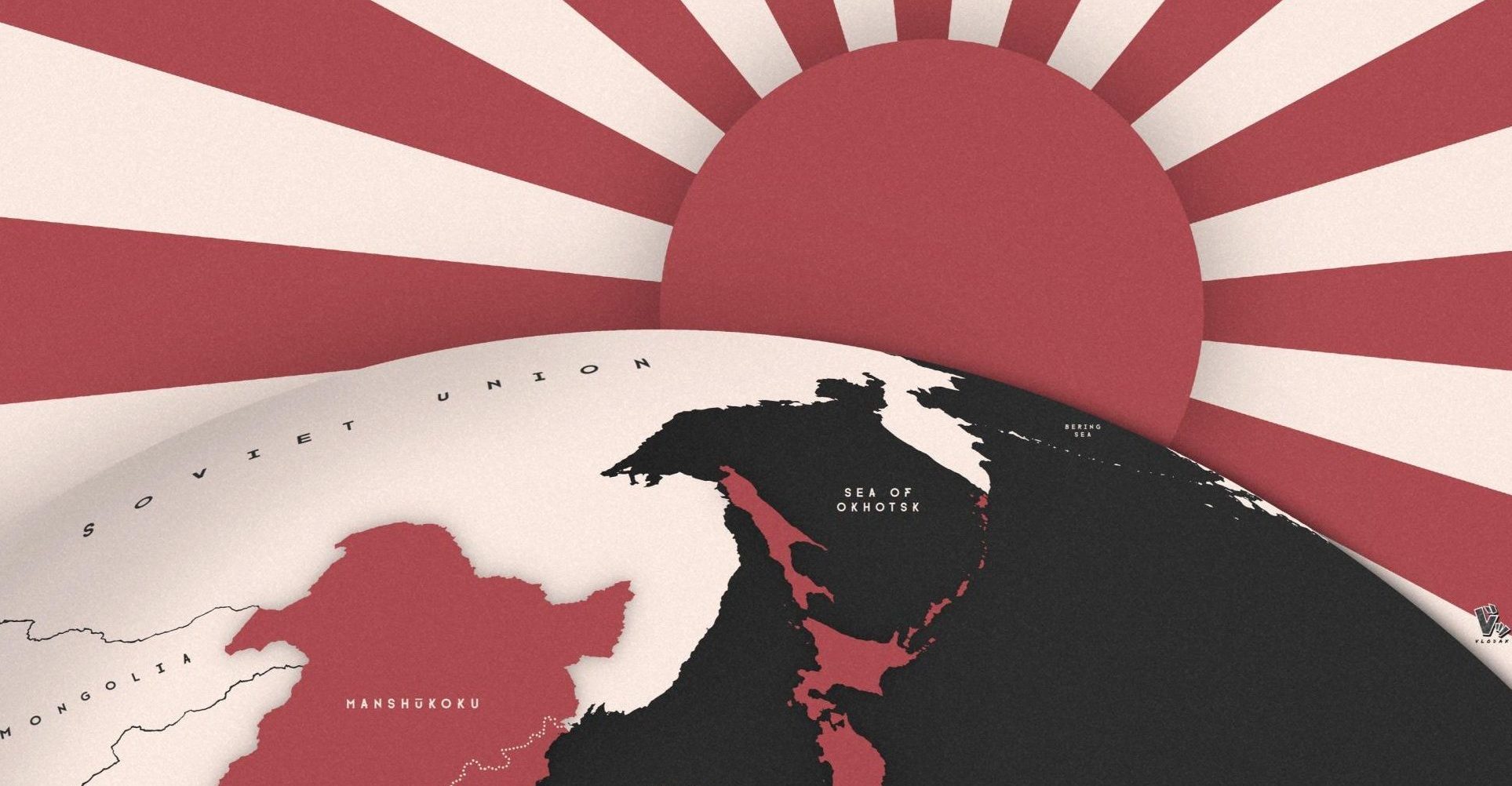

The Empire of Japan will forever be remembered as one of the most formidable and widely feared empires in history. It was neither the biggest nor the most powerful nation of its time, but the unwavering nationalism and radicalism of its people was what set Japan apart. In the decades leading up to World War II, all levels of Japanese society were dominated by an unwavering, almost unnatural, devotion to the state that stood truly unrivalled. When we think of authoritarian regimes throughout history that attempted to radicalise and indoctrinate its people, our minds often drift towards Nazi Germany, who we often consider the pioneers of modern propaganda.

Yet the nationalism of the Japanese was so extreme and so fundamentally ingrained in their culture that it is almost incomparable to that of the Germans or indeed any other nation of the time. It drove seemingly ordinary soldiers to willingly committing horrific atrocities in the name of their emperor. After all, no other nation could even dream of setting up something like Japan’s infamous Kamikaze units, in which soldiers flew suicide attacks into enemy ships. The Japanese truly believed that they were the superior race in Asia and prioritised the longevity of the empire over their own lives. Many gladly sacrificed themselves to better serve the emperor’s cause. The truly unparalleled radicalism of Imperial Japan is due to a variety of factors, which I will try my best to explain here.

The Meiji Era

The roots of the intense Japanese nationalism seen in World War II lie in the ‘Meiji era’, a period between the late 19th and early 20th centuries in which the empire experienced vast economic growth and rapid industrialisation. On 3 February 1867, the 14-year-old Prince Mutsuhito ascended the throne after the death of his father, Emperor Kōmei. Mutsuhito, later known as Emperor Meiji, immediately set out to abolish the shogunate, a hereditary military dictatorship that ruled Japan, and merged its powers with those of the emperor. He recognised that Japan was an underdeveloped feudal society that was at risk of being colonised by Western powers, and introduced a series of radical social and political reforms. This included the introduction of a constitution, ownership of private property, construction of railroads and increased investment in the military, in an attempt to modernise the empire.

The ensuing Meiji era transformed the empire into a great power with a formidable military. Japan’s industrialisation was the fastest of any nation in history, and ended with the death of Emperor Meiji in 1912. The Japanese army benefited greatly from the advancements of the Meiji era, and its decisive victory against the Russian Empire in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904 proved that its strength and sophistication was now comparable to that of any great Western power. This restored much of the national pride that the empire had lost in previous decades, when it was repeatedly defeated and humiliated by Western powers such as the United States.

Nationalism

The Meiji leadership was intent on harnessing the devotion of the Japanese people, and decreed through the new constitution that allegiance to the state was a citizen’s highest duty. The government conveyed this by popularising the motto Fukoku kyōhei (enrich the country and strengthen the military). The Meiji era saw the rebirth of bushidō (the way of the warrior), which was a set of rules that samurais traditionally followed, such as choosing to die honourably rather than surrendering to the enemy. Japan’s education system quickly integrated bushidō, which became a fundamental belief of the military. This further fed into the ideological extremism of the Japanese people as well as the youth.

Thee Meiji leadership corrupted the traditional Japanese religion of Shinto into a sort of ‘State Shintoism’ to better serve the empire, which taught that the Japanese emperor was sacred and comparable to a deity. Students were expected to perpetually recite their oath to serve the state and protect the emperor, and portraits of the emperor were distributed to the Japanese people for ritualistic worship. While the Meiji era may have transformed Japan into a modern industrial power, it returned the empire to its traditional beliefs system of nationalism and intense devotion to the emperor. Perhaps most importantly, it took advantage of the impressionable youth.

Military Extremism

The extremist Japanese military was perhaps the most pivotal factor in the radicalism of Imperial Japan. The establishment of the Imperial Japanese Army Staff in 1878 meant that the military could act independently from the civilian government and the prime minister, reporting directly to the emperor. This meant that the plans of the General Staff were completely free from the strict regulation and oversight of the government, making the military very much a breeding ground for radicalism in Japan.

Throughout the 1930s, they began to grow increasingly dissatisfied with the democratic government of Emperor Taishō after it signed a series of treaties that severely limited Japanese naval power, such as the Washington and London Naval Treaties. This negative sentiment towards the government, coupled with extremist ideology in the military, culminated in a group of junior naval officers assassinating Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi. This ended the brief period of democracy in the Japanese Empire. The military now had almost absolute control over Japanese foreign policy, and sought to establish Japan as a resource-rich empire that was comparable to the colonies of the great Western powers. But natural resources were scarce in the Japanese home islands, so their sights turned to Manchuria, a region in Northeast China abundant in iron and coal that could sustain the rapid growth of Japan’s military.

Nanjing Massacre

The nationalistic dream of unifying Asia under Japanese rule, coupled with the radical Japanese military’s desire for conquest and imperialism, caused Japanese forces to attack Shanghai in January 1932. This would ultimately devolve into a full-scale invasion of the Republic of China in July 1937 and the capture of its capital city, Nanjing. The ensuing Nanjing Massacre was a testament to the depravity of Japan’s deeply radicalised and ethnocentric military, in which they executed Chinese soldiers, raped the women and held killing contests. The unchecked authority of Japan’s armed forces played a crucial role in the radicalisation of the empire and ultimately set the stage for World War II.

Propoganda

The Japanese were masters of propaganda, and used this to great effect throughout World War II to strengthen the nationalism and resolve of their people. While propaganda was prevalent during the Meiji era, the outbreak of World War II and the Attack on Pearl Harbour significantly exacerbated its use as a means to influence the Japanese people. The state instructed magazines and newspapers to describe the evil and corruption of Western powers, in particular Britain and the United States, while militaristic cartoons portrayed the triumphs of the Japanese army over foreign aggressors. The government recognised that indoctrinating the youth would be pivotal in controlling the Japanese people, and taught students about the moral superiority of the Japanese race in a curriculum centred around unwavering loyalty to the emperor.

But most notably, Japan used propaganda to promote conformity and civil unrest in opposing nations. This was most evident in the widespread screening of Japanese films in Chinese theatres, which portrayed Japan as the glorious, virtuous saviour of Asia. Japan sought to achieve an ideological blending of Chinese and Japanese culture through media. As such, they used these propagandistic films extensively to display the greatness of the empire to the Chinese people. Meanwhile, Japanese planes would drop leaflets in European colonies that they intended to invade such as India, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines. These leaflets would describe the superiority of the Japanese over their European colonisers and encourage them to revolt. The use of propaganda throughout Japan stoked the fire of radicalism, and aided the empire’s wartime dream of unifying Asia under its rule.

Read more: The Insight Corner